The epic narrative of the events at the battlefield of Rencesvals in 778 incorporates at least ten specific adjustments, variations or amendments to the historical account, tailored to appeal to the tastes and expectations of a medieval audience. This literary adaptation enhanced the story's dramatic and heroic elements, effectively reshaping the historical facts to suit the epic form and the cultural context of the time:

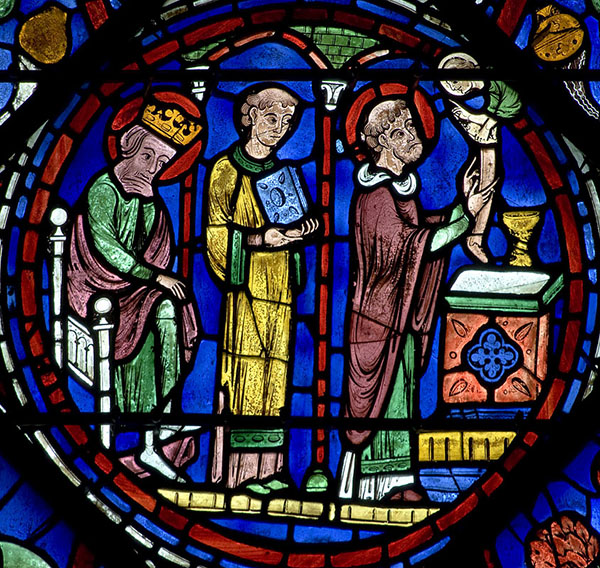

- Objective and nature of the campaign: The Chanson omits the Diet of Paderborn of 777 and does not address the geostrategic goal of establishing the Marca Hispanica to serve as a military and political bulwark against the incursions of the Emir of Cordoba beyond the Garonne River. Drawing on other medieval literary traditions, such as those compiled in the Codex Calixtinus, the campaign in the Chanson is portrayed as a divine mandate, communicated by Saint Gabriel to the emperor. This shifts the focus entirely to the emperor's desire to Christianize Western Europe, framing the campaign unequivocally as a holy crusade.

- Identity of the combatants: The Chanson transforms the historical Basques into Muslims to place the battle within the context of the crusades, which catered to both religious and political interests, and made the narrative more appealing to potential backers and the general public of that era. Muslims were depicted as "the perfect enemy" for the European audience of that century.

- Number of enemies: The actual battle saw the Basques greatly outnumbered, but the Chanson switches the proportions and exaggerates these numbers to a ratio of 1 to 20, with 400,000 Muslims facing 20,000 Franks led by Roland, which intensifies the epic's drama and underscores the heroism of Roland and his men.

- The battlefield: The historical Pass of Rencesvals, characterized by a beech forest, is reimagined in the epic as a fearsome gorge flanked by towering mountain peaks and shadow-filled valleys. The Chanson paints this landscape as a nightmarish, almost ghostly field, setting the stage for an impossible defense, which further dramatizes Roland's last stand.

- Tactics of the enemy's assault: Popular epic tradition has embedded the image of a Muslim attack from the heights of a daunting gorge. This tactical advantage is the only plausible explanation given in the epic for the overwhelming defeat of the Frankish army, highlighting their inability to defend against massive stones hurled from above by an enemy depicted as both cunning and cowardly.

- Focus of the enemy attack: The Chanson places Roland and his peers at the head of the Carolingian army’s rear guard. This literary device strategically removes Charlemagne from the battlefield, maintaining his image as an undefeated Christian hero, reinforced by Roland's refusal to sound the oliphant for help.

- Characterization of Charlemagne: The epic depicts Charlemagne as an old and wise emperor, whereas historically, King Charles was about 30 years old in 778. This campaign was one of his first major military setbacks and marked the beginning of his long military career, which included at least 38 significant campaigns.

- The emperor's rescue efforts: A key narrative choice was to distance the king from the battlefield, and notably, the epic avoids any implication that he fled, leaving his men to a certain death. Instead, it describes Charlemagne's return to the battlefield to recover and honorably bury his men’s bodies.

- Outcome of the battle: The epic constructs a narrative of victory, where the second, entirely fictional part of the Chanson describes the champion of Christendom conquering the entire Iberian Peninsula. This victory narrative plays into the medieval European scribe’s dichotomy of good versus evil.

- Impact of the epic narrative and the legend of Rencesvals: This is a crucial question that sheds light on a longstanding historiographic debate, which has persisted for at least 340 years since the publication of the Fifth Book of the Annales del Reyno de Navarra by Joseph Moret in 1684. These revisions and dramatizations crafted a compelling and resonant epic, which not only glorified Charlemagne and his knights but also significantly influenced both historiography and popular culture, molding perceptions of this historical event for centuries.

Each literary device employed in the song serves a specific purpose, drawing from oral traditions to compose a narrative of remarkable power and resilience. The Song of Roland continues to captivate modern readers with its vigorous, dynamic, and idealistic portrayal of its characters and themes. It is crucial to recognize that while history can and should be conveyed accurately, art thrives on the freedom to transcend the factual—to reimagine people, places, and events for profound emotional and cultural impact. This creative liberty enriches the narrative, making it a timeless piece that not only tells history but elevates it to the realm of legend.

Therefore, the answer to the question of what influence the Chanson de Roland and the collection of legends and traditions that have developed around the Battle of Rencesvals and the figure of Roland have had should arguably be "none". Yet, this is not the case. The Chanson is a beautiful epic piece with incalculable literary value, but it is not a historiographical source. Unfortunately, many modern and contemporary authors have used the poem as a source of historical information, referencing Muslims, an attack on the rear guard, the dark gorges of the Pyrenees, and the hurling of huge stones, among other details of a purely literary nature. Anyone who has visited the site of the battle would understand that slings are impractical weapons in a dense beech forest. The issue is not with literary creativity; the problem arises when historiography is based on legendary facts.

This point was highlighted by one of the fathers of modern European historiography, the Jesuit Jose Moret, a chronicler of the Kingdom of Navarre. Juan de Mariana published the Historia de rebus Hispaniae in Toledo in 1592. Nine years later, in 1601, the work saw its first Spanish edition under the title Historia general de España. Following this initial Latin edition, the work was reprinted in Madrid in 1608, 1617, 1623, and 1650. As Jose Moret stated, Mariana discussed the Battle of Rencesvals in Book 7, Chapter 11 of his Historia general de España "with so little knowledge of the historical events of that time" that the account is riddled with substantial and numerous errors and, what's worse, the narration deviates from the truth, prompting Moret in 1684 to call for its correction. In his work Castigaciones de la historia de Navarra por el padre Juan de Mariana, Moret describes how Mariana chose not to use or refer to any of the Carolingian chronicles nor did he cite them in his bibliography. In fact, he was well aware of some of these documents but deliberately chose not to utilize them, opting instead to base his narrative on medieval legends. Furthermore, Mariana asserted in the Latin edition of his work that Einhard had omitted to mention the Battle of Rencesvals in his annals, which is untrue; Einhard did indeed reference the events of 778 in great detail.

Mariana’s decision to rely on legends documented in the Historia Caroli Magni et Rotholandi, a 12th-century literary text included in the Codex Calixtinus, has led to a long historiographical tradition that has been either transformed or distorted by myth. This shift from historical accuracy to legendary embellishment highlights the complex relationship between historical facts and their literary representations, significantly influencing how these events are perceived and understood in historical discourse. The foundation of history should solely be facts, as this provides the closest approximation to the truth that we can achieve.