The poem is structured into two primary parts, each further subdivided into two sections.

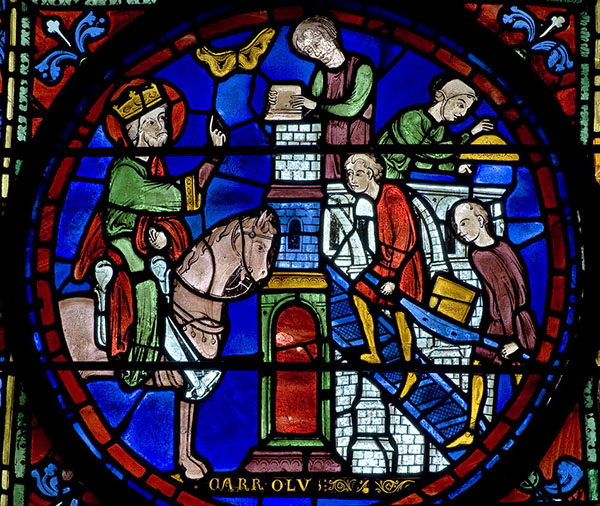

The first part, which is heavily rooted in historical context, spans from laisses or stanzas 1 to 176 and includes several divisions. The first section (stanzas 1 to 52) deals with the negotiations for Zaragoza's surrender and the betrayal by Ganelon. After seven years of crusading, Charlemagne has subdued most of Hispania, which was previously under Muslim control, with Zaragoza being the last city to resist under the reign of King Marsile. A dubious embassy led by Blancandrin arrives, proposing the city's immediate surrender and the conversion of Marsile and his vassals to Christianity. The assembly of Frankish nobles persuades Charlemagne to agree to Marsile's terms. Roland nominates his stepfather Ganelon to represent Charlemagne at Marsile's court. Suspecting Roland's intention to endanger him—as Marsile had previously ordered the assassination of two Frankish envoys—Ganelon plots revenge. Seduced by Blancandrin's words, Ganelon orchestrates a scheme to kill Roland, the primary aggressor against the Muslims. He suggests to Marsile that by feigning submission, the Muslim forces could ambush the Frankish rearguard at Rencesvals Pass, commanded by Roland and the twelve peers, once Charlemagne’s main forces have withdrawn. Trusting Ganelon's counsel, Charlemagne appoints him to manage the rearguard, placing his nephew Roland in perilous command.

This section sets the stage for the ensuing tragedy and frames the historical backdrop against which personal and political conflicts unfold, driving the epic narrative forward.

The second section (stanzas 53 to 176) focuses on the harrowing battle and the deaths of the twelve peers at Rencesvals Pass. As Charlemagne and his main forces cross the Pyrenees, the vast army of Marsile launches a fierce assault on the rearguard commanded by Roland. Despite the prudent Oliver's three urgent warnings about the imminent danger and his advice to signal their critical situation to the emperor by sounding his oliphant, Roland, in his reckless pride, refuses to call for help. He believes that to do so would stain his honor, preferring to face the overwhelming odds with just his loyal band of knights.

Roland and his men bravely withstand two intense attacks from the enemy, demonstrating formidable courage and skill. Yet, the cost is steep; the Frankish knights are gradually overwhelmed and slain by the vast number of Muslim warriors. As the battle rages, Roland finally realizes the necessity of summoning aid and attempts to blow his oliphant. By this time, however, Oliver, recognizing the futility of their plight, counsels against it. Ignoring Oliver’s advice, Roland blows the horn with such force that he bursts his temples, a fatal effort born from desperation.

In the tragic conclusion of the battle, after Oliver's death, the remaining heroes, including Archbishop Turpin and Gualter del Hum, fall one by one. Left alone on the battlefield, Roland faces his end with defiance. In a final act of valor, he attempts to destroy his sword Durandal, which contains a thousand holy relics in its hilt, to prevent it from being captured by the enemy. Despite his efforts, the sword remains intact when the stone he strikes shatters under the force of his blow.

Roland dies a heroic death, facing the western lands he had conquered. As he passes, God extends His right glove, and Saint Gabriel descends to escort Roland's soul to Paradise, honoring his sacrifice and valor. This climactic sequence highlights the epic's rich tapestry of bravery, loyalty, and fate and reinforces the thematic resonance of divine justice and the heroic ideal.

The second part of the poem, which is entirely fantastical and lacks any historical foundation, spans from stanzas 176 to 291. This segment is also divided into two distinct sections.

Stanzas 176 to 267 detail Charlemagne's grim return to the battlefield and the comprehensive defeat of the Muslim forces along the banks of the Ebro River, culminating in the capture of Zaragoza. As Roland lies dying, he calls upon heaven for aid, and in response, Saint Michael descends to protect Roland’s soul. This divine occurrence initiates a series of supernatural events where Saint Michael, alongside Saint Gabriel, battles the forces of evil that attempt to claim the souls of the fallen knights. The archangels ensure that these souls do not fall into enemy hands, symbolically preserving the purity and heroism of the Frankish warriors even in death. Upon hearing the distant sound of Roland's oliphant signaling for aid, Charlemagne immediately suspects Ganelon of treachery and orders him to be chained. The emperor quickly makes his way back to Rencesvals Pass, where he is moved to tears by the sight of the fallen heroes. He commands that the bodies of these valiant knights be transported back and buried in France, their homeland, to rest in honored graves.

Charlemagne then leads his army in pursuit of the retreating forces of Marsile. He catches up with them by the Ebro River and decisively crushes the remaining troops. In a pivotal confrontation, Charlemagne faces Baligant, the emir of Babylon, who has come to aid Marsile. The battle is fierce, but Charlemagne emerges victorious, slaying Baligant and subsequently taking control of Zaragoza. News of this defeat reaches Marsile, who succumbs to his injuries—inflicted by Charlemagne— and dies, his soul damned to hell by demonic forces.

Following these events, Charlemagne ensures the fallen are honored: Roland, Oliver, and Archbishop Turpin are interred in the church of Saint-Romain in Blaye. The emperor then returns to Aachen, weighed down by sorrow and the heavy losses of war. Tragically, Alde, Roland's beloved and Oliver's sister, dies of grief upon learning of Roland's demise, her heart broken by the overwhelming loss. This sequence of events underscores the high cost of victory and the profound impacts of loyalty and betrayal woven throughout the epic.

Stanzas 268 to 291 of the poem narrate the aftermath of the battle, focusing on the return to the palace and the trial and execution of Ganelon, who is branded a traitor. Despite Ganelon's undeniable betrayal, during his trial, he argues that his actions were motivated by a desire for revenge against Roland, who he claims sent him into a perilous situation that was sure to result in his death. He contends that his decisions were justified and calls for divine judgment to prove his innocence. However, his defense is unsuccessful; the champion defending Ganelon, Pinabel, is defeated by Thierry of Anjou, who champions Roland's cause.

Following the duel that seals his fate, Ganelon is sentenced to a brutal execution: he is to be quartered, tied to the limbs of four horses that pull him apart. This grisly punishment I shown as proportional to the gravity of his treason. In the midst of these events, the archangel Saint Gabriel delivers a divine command to Charlemagne, instructing him to gather his armies and initiate a new Crusade. This holy war is to support King Vivian at the city of Orfa, now threatened by infidel forces.

The first part of the poem, stanzas 1 to 176, though rich with epic embellishments, is grounded in historical references that inform the narrative foundation. The real military campaign led by Charlemagne in the Ebro Valley in 778, which spanned approximately seven months from his departure from Douzy to his arrival at Auxerre, is transformed in the epic into a protracted seven-year crusade. This artistic alteration not only magnifies the scale and significance of the conflict but also enhances the heroic stature of Roland, who in the poem commands the same number of men—20,000—that comprised the historical Carolingian army. Such exaggerations are typical of the poem's style, employing hyperbole to elevate the historical campaign to a war of Homeric scale, thereby intensifying the epic's dramatic and thematic impact.

|

Charles the King, our Lord and Sovereign, Full seven years hath sojourned in Spain, Conquered the land, and won the western main, Now no fortress against him doth remain, No city walls are left for him to gain, Save Sarraguce, that sits on high mountain.

|

King Charles, our Lord and Sovereign, Has spent a full seven years in Spain, Conquering the land and claiming the western sea, Now no fortress remains to challenge his reign, No city walls stand to be won, Except for Saragossa, set upon a high mountain. |