Nothing can be that which it is not. Nothing exists without its inherent nature, and by definition, literary works are not sources of history. Contemporary authors are unable to construct historiographic essays on the Battle of Rencesvals solely based on the Chanson de Roland. The epic, while rich in narrative and character, lacks the factual accuracy and comprehensive detail required for historical analysis. It simply serves other purposes. The Chanson, though invaluable as a cultural artifact and a window into the medieval mindset, cannot be used as a source for writing historiographic essays about the battle.

Nonetheless, distinguishing between the historical chronicles of the eighth century and the literary traditions carried by epic poems can often be challenging. While the former compiles historical data and sifts through events that may obscure the overall narrative, the latter enriches historical facts with elements that transform reality into legend. Both, however, weave threads of realism and fiction into their narratives.

"The Song of Roland" is an epic poem composed of several hundred verses, penned towards the end of the 11th century—around three centuries after the events it describes. The Oxford manuscript credits its authorship to a Norman monk named Turoldus. It stands as one of the earliest pieces written in a Romance language in Europe, highlighting the significance of the battle—one of Charlemagne's rare defeats.

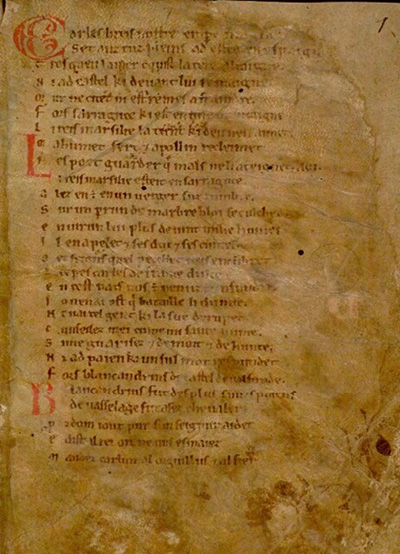

The oldest surviving copy of "The Song of Roland" is the Digby 23 Manuscript housed in the Oxford Bodleian Library, penned in Anglo-Norman between 1140 and 1170. Anglo-Norman was a language used in England and is a variety of the Norman dialect, which evolved distinctly due to the political and social structures in England after the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The text likely predates these manuscripts and consists of 4,002 lines distributed in 291 stanzas of unequal length called laisses. This particular manuscript is notable for being owned by a minstrel who utilized it during public performances, lending the document unique historical value.

Indeed, the Digby 23 Manuscript falls into the category of "manuscrit de jongleur" (jongleur manuscripts), a term coined by Leon Gautier. The "manuscrits de collections" (collection manuscripts) were luxurious copies kept in libraries more for display than reading and, not without some pride, for showing to friends. In the early fourteenth century, it was very common for good libraries to like to have copies of songs and other medieval literary works. Instead, jongleur manuscripts were practical tools used by minstrels for performing epic poems. These manuscripts often included mnemonic aids to facilitate recitation across various venues. Due to their intensive use, such manuscripts rarely survived; Gautier himself expressed concern over the dangers these manuscripts faced on the treacherous roads of the Middle Ages: "I really tremble at the thought that the Oxford manuscript containing the famous Song of Roland ran such great dangers on the poorly assisted roads of the Middle Ages."

Although Charles Samaran, who conducted the first codicological analysis of the document in 1932, questioned Gautier's evaluation, both scholars agreed that the manuscript's poor material quality, compact and manageable size, and evident signs of frequent use all suggest that it was indeed utilized by a minstrel.

A peculiar aspect of the Oxford manuscript is the enigmatic "AOI" formula, absent in other medieval manuscripts but repeated across 172 of the 291 stanzas. This formula, usually placed at critical narrative moments or stanza ends to indicate changes in the mood of the characters or inflection points in the course of the story itself, likely served as a rhythmic or melodic cue for minstrels to maintain lyrical consistency. In fact, the AOI formula typically appears at the end of the final verse of a stanza or laisse; however, there are 21 instances where this is not the case. The number of verses between two AOIs slightly varies, suggesting a somewhat regular pattern, though not a fixed or unchanging one. This variability indicates that the AOI likely served as a rhythmic or melodic guide to help the minstrel accurately start each new melodic phrase of the Song. Alternatively, it may simply be an abbreviation of "amen."