The Basque Country in 1936

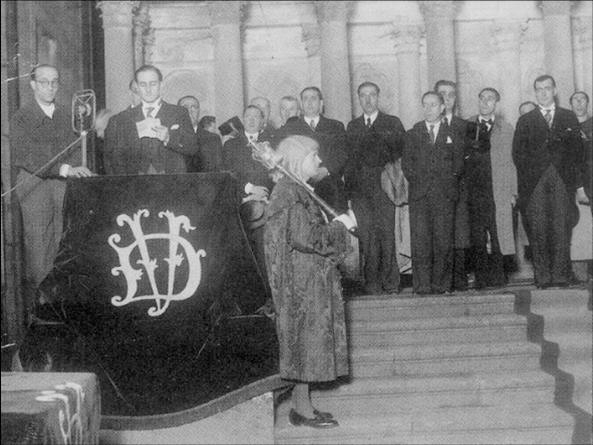

Basque president Jose A Agirre took the presidential oath of office in October 1936 in Gernika

Since the abolition of the Basque historical laws (the fueros) in 1876, the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV) claimed the devolution of the historical rights of the Basques, which in political terms meant independence. After the proclamation of the Spanish Republic in 1932, two autonomy statute projects promoted by EAJ-PNV and the Basque Nationalist Action (ANV-EAE) party were killed by the Spanish parliament. Finally, after the approval of the statute of autonomy on October 6, 1936, Jose Antonio Agirre was elected Lehendakari (president) of the Basque autonomous state and was sworn in a day later in Gernika. A government of democratic concentration led by EAJ-PNV was formed, including all political parties.

Despite not being part of the leftist Popular Front and being a Catholic party, EAJ-PNV firmly positioned itself against the uprising since the Basque Nationalism did not have any religious or political connections with the rebels. The National Movement (Franco’s governing institution established in 1937) represented totalitarianism versus the Basque democratic republicanism; political centralism and Spanish radical nationalism versus the defense of the political and cultural rights of the Basque people; and, finally, a hierarchical and doctrinaire Catholicism, far from Maritain’s Christian-democratic ideology held by the Basque nationalists.

The confrontation was inevitable, and the first air war action on Basque soil, the bombing of Otxandio, took place on July 22, 1936, just four days after the Spanish military uprising and three days after the deputies of EAJ-PNV, Manuel Irujo and Joxemari Lasarte, announced by radio their political party’s unequivocal and explicit rejection of the ideological positions and military strategy of the conspirators.